In short

The story of the Rohingyas is the story of one of the most persecuted people in the world. One of Myanmar’s ethnic minorities, the Rohingya come from the Rakhine state, a borderland with Bangladesh in Western Myanmar. They are Muslims, and they are not recognized as citizens in any country. In 2012, the rape and killing of a young Buddhist woman provided the casus belli for clashes, later escalating into a violent conflict that caused deaths, people missing, and the plundering and destruction of entire villages. In 2017, further clashes with the Burmese army led to an ethnic cleansing operation, generating a massive migratory wave in all neighboring countries.

The origins of the Rohingya people

The origins of the Rohingya (as of today, approximately around one million) are lost in history. According to some theories, the Rohingya’s presence in Myanmar is centuries old; other theories assume that this ethnic group only migrated to the country in the last century. Certainly, the Rohingya’s existence in today’s Myanmar was documented in 1785, when the Burma invasion of the then-Arakan area (as the Rakhine state was initially named) killed thousands of native people, among which many Rohingyas. Those who managed to escape took refuge in the bordering areas, mainly controlled by the British, leaving the land almost empty.

Subsequently, the British colonization of the Arakan, a fertile region, encouraged many to migrate from the neighboring areas. Thousands of Rohingyas migrated from Eastern Bengala – today’s Bangladesh – to Arakan. The British Censuses referring to the Akyab district show that, in 1871, 58.263 Muslims lived in the area, increasing to 186.323 by 1911 due to cheap labor needed in the British East India Company’s lands.

A stateless people

In 1948, Myanmar gained independence. In 1962, a military coup overturned the Burmese government. After the coup, a military junta governed Myanmar for almost half a century. During those years, the Rohingya suffered significant discrimination due to the harsh nationalism of the authorities, which defined them “ugly as ogres” individuals, entirely alien to Myanmar. Things did not change with the end of the military government: today, the Rohingyas are still a “stateless people”.

In 1982, the military government enacted the Citizenship Law, excluding the Rohingya from the country’s recognized ethnic groups and classifying them as illegal foreigners. Stripped off of their citizenship rights, the Rohingya are vulnerable and subjected to discrimination. Even Bangladesh, a country in which many took refuge from violence, denies them citizenship and is now unable to welcome them.

Being a Rohingya: violence and discrimination

Being a Rohingya in Myanmar is hard. A special permit is required to travel and move around, even for necessities such as job searching, trading, going to the doctor, or attending a funeral. In some areas, it is forbidden to have more than two children per family. Many Rohingya are pressed into forced labor, face arbitrary arrests, property seizures, discriminatory taxation, and physical and psychological violence. Finally, young Rohingya are denied the right to education.

Even Buddhist monks play a role in such segregation: some consider the Rohingya to be an ominous menace for the Buddhist religious purity. On these grounds, many Buddhist monks forbid mixed marriages and boycott Rohingya’s shops, giving rise to a worrying level of incitement to hatred. The so-called 969 Movement – whose official anthem includes lines such as “they live in our land, drink our water, and are ungrateful to us” – is led by Ashin Wirathu, a Buddhist monk. Wirathu spent eight years in jail on charges of incitement to hatred and was later released under an amnesty. With reference to the Muslims, Wirathu repeatedly said that “you can be full of kindness and love, but you cannot sleep next to a mad dog”. Such discrimination turned into actual ethnic cleansing operations at the hands of the Burmese State in 2017, following the violent clashes between the Burmese army and some Rohingya extremists in the Rakhine territory.

From violence to genocide

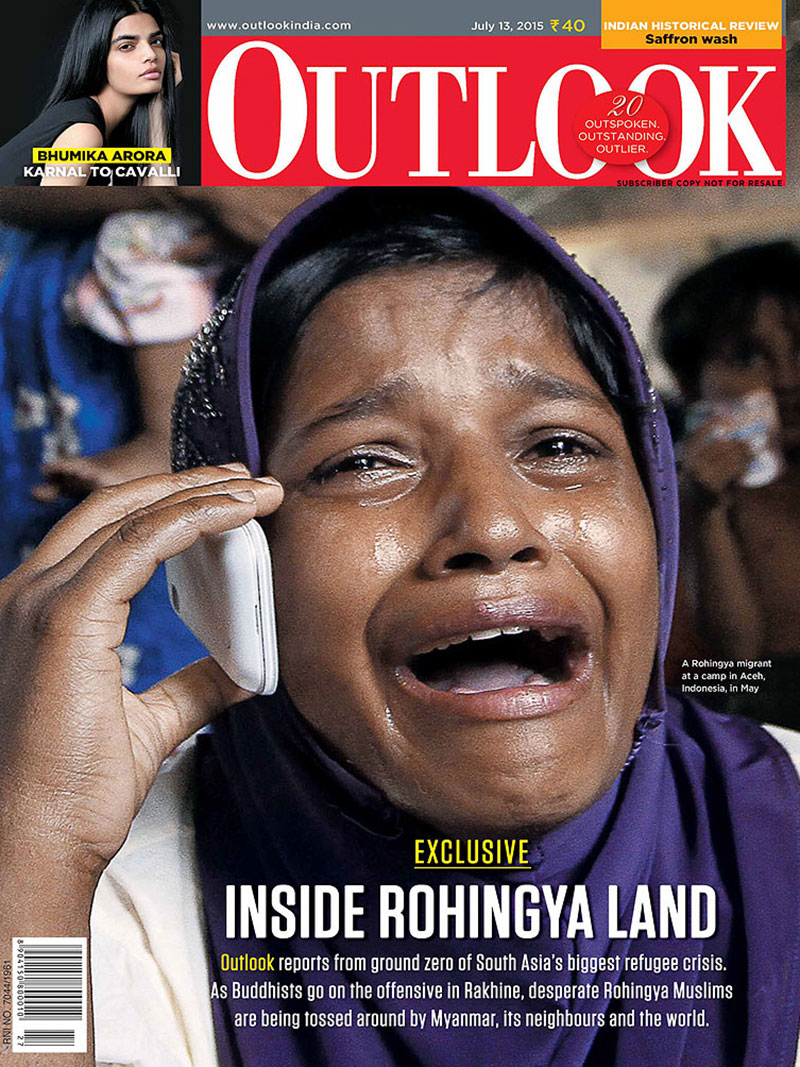

In 2012, the rape and killing of Thida Htwe, a young Buddhist woman, sparked an outbreak of violent clashes and a new wave of violence against this Muslim minority, which put the Rohingya question under international limelight. There have been more than 600 deaths, thousands of missing people, and many villages were destroyed. These events intensified the outflow of Rohingya refugees, which reached the first peak in 2015: around twenty-five thousand refugees left the Bay of Bengal, generating a real migration emergency that was aggravated by hostile attitudes and policies from the neighboring countries.

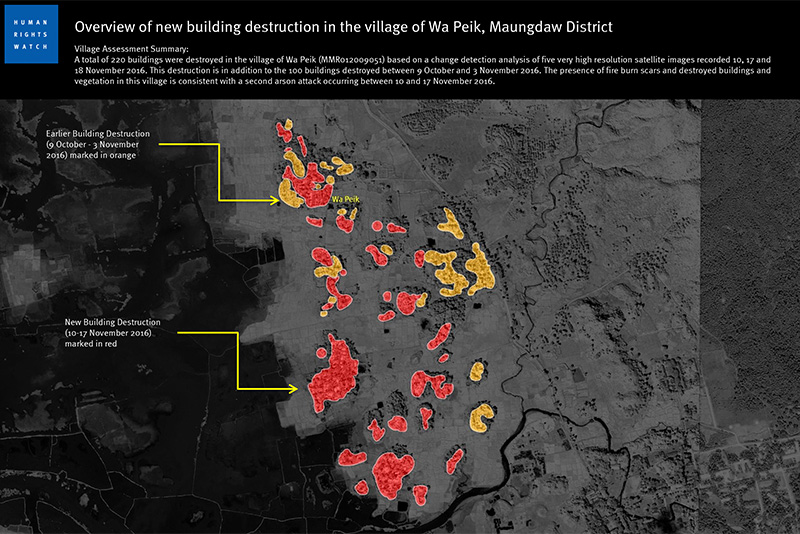

Following some armed attacks to the checkpoints in Rakhine at the hands of the ARSA (Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army), the Burmese army carried out a systematic repression of the Rohingya, involving massacres, rapes, systematic burnings, and crimes against humanity.

Since August 2017, more than 730.000 Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh, settling down in refugee camps on the border. Bangladesh and Myanmar later signed a bilateral agreement to repatriate the Rohingya starting in 2018, but Bangladesh delayed the repatriation amid protests from human rights groups.

From May 2018 to May 2019, only 185 Rohingya refugees were repatriated in Myanmar, 31 of whom had returned of their own volition. Myanmar authorities accuse Rohingya militants and Muslim organizations operating in the refugee camps of dissuading people from going back. Yet, it seems that Myanmar’s unchanged life conditions for the Rohingya, with ongoing discrimination and violence, is the main reason many refugees refuse to return to Myanmar.

In 2018, the United Nations defined the violence against the Rohingya as an example of ethnic cleansing; in the same year, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) concluded that a substantial and severe risk existed that genocidal actions directed at the Rohingya might recur. For this reason, the OHRHR made concrete recommendations that Myanmar should be investigated and prosecuted in an international criminal tribunal for genocide.

Aung San Suu Kyi’s role

The Peace Nobel Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi – State Counselor of Myanmar and Minister of Foreign Affairs from 2016 to 2021 – has always had an ambiguous position on the Rohingya question.

After the outbreak of violence in 2012, Aung San Suu Kyi repetitively avoided mentioning the Rohingya in official speeches and interviews, simply inviting people to “respect law and order” and rejecting the name “Rohingya”, rather calling the refugees “Bengalis” or “Muslims”.

Despite the calls from important figures like Desmond Tutu, who asked Aung San Suu Kyi to protect the Rohingya Muslim minority (“a country that fails to protect the dignity and worth of all its people is not a free country”), the Lady, as Aung San Suu Kyi is known, has been holding a contradictory position with the Rohingya question.

In 2017, the United Nations Human Rights Council established the Independent Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar (IIFFMM) to clarify the facts and circumstances of the violence and human rights violations in Myanmar. The mandate, which ended in 2019, has not only assessed several violations of international law; it also concluded that the Burmese leader Aung San Suu Kyi “has not used her de facto position as Head of Government, nor her moral authority, to stem or prevent the unfolding events, or seek alternative avenues to meet a responsibility to protect the civilian population”.

All this has undermined international confidence in Aung San Suu Kyi as a Nobel Prize Laureate. In 2018, Amnesty International announced that it had withdrawn the Ambassador of Conscience Award, Amnesty’s highest honor, from Aung San Suu Kyi.

Time, July 1st, 2013

Outlook, July 13th, 2015

Newsweek, August 8, 2018

Today

In December 2019, Aung San Suu Kyi traveled to the International Court of Justice at The Hague, facing allegations of genocide against the Rohingya by the Burmese government. The case was brought to the ICJ by a court of Gambia, a Muslim west African state: listening to survivor’s stories, the Gambian Justice Minister Abubacarr Tambadou said that Myanmar violated the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, and that those stories reminded him of the events in Rwanda.

In January 2020, the UN’s top court ordered Myanmar to take measures to protect the Rohingya from genocide, defining them as “members of a protected group under the Genocide Convention”.

On February 1, 2021, Myanmar witnessed a coup d'état, in which the army seized power and arrested the Burmese leader Aung San Suu Kyi. As a result, the country has plunged into a humanitarian catastrophe, with violence and arrests increasing the fears for the Rohingya minority and Burmese civil society as a whole.

On Monday, July 12, 2021, the United Nations Human Rights Council adopted a resolution condemning the Myanmar military's human rights violations against the Rohingya and other minorities. The resolution calls for an immediate cessation of hostilities, attacks on civilians, and humanitarian laws and rights violations in the state.