A high-powered letter bomb exploded in the rooms of the sociology department of Maputo University in Mozambique on 17th August 1982, killing white anti-apartheid sociologist and activist Ruth First on the spot. However, her research and political analysis would give a decisive thrust to South Africa’s path to freedom.

Ruth First’s heritage of values came from afar, from a distant past when her grandparents lived a life of poverty and deprivation in the late 19thcentury, when they left Lithuania and arrived in South Africa to escape the anti-Jewish persecution of the tsarist empire. From a young age, Ruth First had distanced herself from the white middle class to which she belonged by birth right. She could easily have drawn the benefits that the apartheid regime ensured to the Afrikaner minority, instead she chose a more difficult and riskier path: that of dissent and political struggle. At university, she assiduously attended student association meetings, taking part in demonstrations, debates and assemblies animated by high hopes that would turn out to be fatal illusions.

Her political and moral choice against racism became an actual commitment in the tragic summer of 1946. In August of that year some eighty thousand exploited black miners went on strike for a week paralysing the world’s largest capitalist federation, the Chamber of Mines. Their demands were rejected by the mining company and state retaliation proved ruthless. Workers were locked up in enclosures under army control, union leaders were arrested and police brutally attacked a march, killing twelve workers and injuring over a thousand. This bloodily suppressed protest convinced young Ruth First to pursue a career as a journalist to denounce the regime’s abuses. In her early twenties, she left her job at Johannesburg City Council’s research department and first crossed the threshold of the local editorial office of the Guardian, a weekly newspaper then close to the Communist Party.

Her husband, Joe Slovo (1926 - 1995), also of Lithuanian descent, married in 1949, was a leading figure in the South African Communist Party (SACP), which in 1989, while remaining convinced of socialist ideals, broke with state communism. He played an important role in the negotiations for the end of apartheid in 1992 and, after 1994 elections, was a minister in Mandela’s government.

The couple, who had three children, were among the first to be labelled as dangerous enemies of the state and to be kept under constant police surveillance. The regime saw them as an incomprehensible anomaly that squared the aseptic organisation of the South African state, where whites prospered and ruled while blacks were plundered, starved, enslaved, imprisoned and finally murdered. For the advocates of apartheid and all those who benefited from it, it was perfectly normal that blacks like Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu tried to rebel, but it was much less understandable that there were whites who had chosen the struggle for equality and civil rights for the entire population.

Over the years, in order to limit her activities, she was banned from leaving Johannesburg, from entering African municipalities, from attending meetings and finally even from writing articles signed by her. However, her activities as a militant journalist continued even after the Guardian was eventually banned under the Communism Suppression Act. Ruth First quickly became one of the most respected theorists in the struggle against apartheid. She was not yet in her thirties when she joined the small group of activists charged with working on the drafting of the Freedom Charter, the historic declaration of intent aimed at creating a “united, democratic and non-racial” South Africa.

Since 1952, the lives of black South Africans had been conditioned by the brutal “pass laws”, which required black people over the age of 16 to show special identification to enter white-only urban areas. It was a cruel form of filing that allowed for new abuses by employers, leading to a nightmare scenario throughout the country. Prisons filled to capacity: in a single year, 1955, some 340,000 black workers were convicted by the courts for pass-related administrative offences. Dissent against the government’s draconian laws was still being expressed peacefully, but the regime clamped down increasingly harder, no longer only through bans and censorship. In December, the largest police operation ever seen in the history of South Africa was launched. Officers stopped and searched more than five hundred people in homes and offices all over the country. Eventually, 156 people were arrested and charged with high treason and conspiracy against the state. The group included all the main leaders of the ANC (African National Congress) and some 20 white militants, including Ruth First and her husband Joe Slovo. The monumental trial to which the group was subjected lasted more than four years in total and ended in acquittal for all, but it was to have decisive and unexpected fallouts on the political confrontation taking place in the country. Soon afterwards, all the leaders of the movement for the emancipation of black people were forced into hiding or exile, were imprisoned or murdered. The repression was extremely harsh and culminated in Sharpeville massacre on 21st March 1960. The police opened fire on unarmed demonstrators protesting against the pass laws, indiscriminately hitting men, women and children. In the end, 69 people were killed and the massacre proved that non-violent struggle was not sufficient to defend the rights and lives of black people. The anti-apartheid movement thus took the road of no return to armed struggle. It was at that time that the fates of Ruth and her husband Joe began to part. He, who had been held in prison for six months during the state of emergency proclaimed after Sharpeville, joined the high command of the paramilitary group (MK) led by Nelson Mandela and for the next twenty-five years was to be one of the main strategists of the armed organisation. Ruth was not opposed in principle to the armed turn undertaken by the ANC but felt it was essential for this to remain subordinate to political struggle. She firmly believed in a revolutionary outlet for society but not to the extent of advocating violent theories. Her only weapons would forever remain study, teaching and field research, even when continuing to live and work in her country became impossible.

In 1961 she managed to circumvent ministerial bans and escaped for a few days to the territory of present-day Namibia, the small country that South Africa had unilaterally annexed immediately after the Second World War. She conducted a meticulous field investigation to analyse the exportation of the South African racial model. Although she was denied access to archival documents, for four days she managed to escape tight police controls and to interview black people of South West Africa, the inhabitants of the “last colony”, which Pretoria government considered to be a mere territorial appendage of South Africa. The material she collected became the starting point for her first book, South West Africa, published in London in 1963. In South Africa its dissemination was strictly forbidden and anyone found in possession of a single copy of the book risked up to five years in prison.

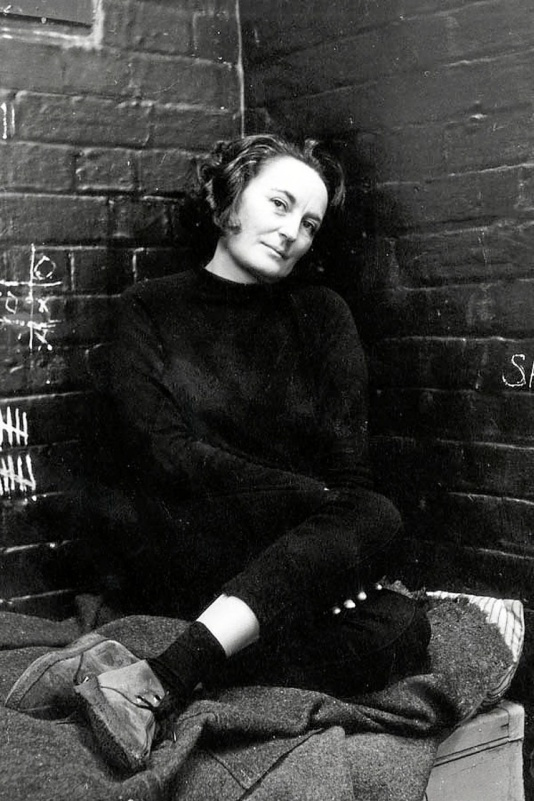

Soon after her return home, Pretoria government banned her from leaving Johannesburg, conducting any form of research or journalist work, and communicating with other banned people. Her work as a journalist had already been effectively precluded to her, as all the newspapers she worked for had in the meantime been censored and then closed down by ministerial order. In an August afternoon in 1963, she was eventually arrested based on the infamous 90-day law that gave absolute power to police, allowing them to detain those suspected of political offences even in the absence of charges. She was subjected to three months of pressure and psychological torture, with interrogations that went on for weeks, in which policemen asked her for information about Joe, the other leaders and the strategies of the movement. At the end of the statutory period of detention she was released but barely made it out of the police station when they arrested her again, still using the 90-day law as a pretext to persecute her. When she returned to freedom, she became convinced that the road to exile was now inevitable for her as well, since in the meantime the few remaining leaders of the movement in the country had ended up in jail or on trial. On 14th March 1964 she left South Africa, unaware that she would never see her country again. She took refuge in London, in a house that became the base of her exile and where she worked at a furious pace, producing essays, articles, pamphlets, speeches. In the late 1960s and early 1970s she edited the biographies of Nelson Mandela, Govan Mbeki and the Kenyan leader Oginga Odinga. In 1965 she published A World Apart, a biographical book in which she documented with disarming lucidity the months she had spent in solitary confinement in prison, which proved to be so successful that the BBC acquired the rights to make a film adaptation. The film titled 117 Days, in which Ruth played the role of herself, was released in Britain in 1966 despite vain attempts by the South African embassy to block its screening.

When she was not writing, she was lecturing around Britain. She took part in dozens of public meetings against apartheid, in which she denounced in no uncertain terms the repressive apparatus of Pretoria regime, extrajudicial killings, the massacres of defenceless civilians. Between 1964 and 1968 she travelled extensively in Africa to analyse the reasons for the failure of independence struggles in Nigeria, Ghana, Sudan, Egypt and Algeria, and to try to understand why those countries were so vulnerable to military coups. This activity established her as a scholar of international standing. After spending a sabbatical year in Tanzania, at the University of Dar es Salaam, she moved to Libya to study the causes and possible consequences of the revolution that had overthrown a corrupt, pro-Western monarchy. But it was in Maputo, Mozambique, that Ruth First spent the last and most fruitful years of her activity as a committed intellectual at the service of a project of human emancipation. In 1977 she was called to direct the Centre for African Studies at the university of the Mozambican capital. The political ideas, passion and gentle power she wielded even in her years of exile continued to represent a danger to the South African government, which never ceased to consider her as a target for elimination. The revolutionary scope of her scholarly work was a threat to the regime.

The fatal bomb that the South African regime detonated in a hot August afternoon in 1982, in the halls of Maputo University, managed to kill her but not to silence her voice. Ten years later, as one of the most dramatic periods in the history of apartheid in South Africa was drawing to a close, a packed ceremony was held in Johannesburg to remember Ruth First on the tenth anniversary of her death. “Her life and her death”, Nelson Mandela stated on that occasion, “remain a beacon for all those engaged in the struggle for freedom”.