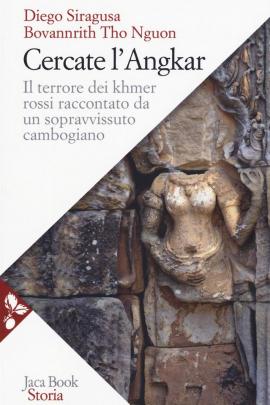

The cover of the book by Bovannrith Tho Guon

To talk about the subject “Remembering and bearing witness to the Good”, I cannot help without describing Cambodia’s recent history, a series of events, which is still little known and that many have forgotten.

On 17 April 1975, about 44 years ago, the Khmer Rouges entered victoriously the Cambodian capital, Phnom Penh, against the regime of Lon Nol, backed by the United States of America. The Khmer Rouges were revolutionaries of communist mould. The term “Khmer Rouge”, communist Cambodians, had been coined by Prince Sihanouk: he had dominated the Khmer political stage from the independence to the French protectorate and the coup by Lon Nol. By a few hours since their conquest of Phnom Penh, the Khmer Rouges forced the population to leave the capital. From the loudspeakers, in a threatening tone, the Khmer Rouge soldiers summoned the people to leave the capital immediately: the danger of bombings by the Americans was imminent, but we all could get back to our homes after a few weeks. We all, quite naively, believed that, and I, who was 13 years old, only thought that I would get a small holiday from school.

My family and I had decided, bringing with us only a few things, to go to my Grandparents’ village, which is situated south of the capital. The road was blocked and we have to change direction, walking along a parallel to the river Mekong. Only after many days, we managed to reach the Grannies’ village by boat. Travelling on foot was exhausting. The eviction of the population from the capital was one of the forced migration of recent history. The hospitals were emptied: many patients died. I then learned that the capital Phnom Penh became a ghost town during the Khmer Rouge regime, which lasted 4 years, from 1975 to 1979, the year in which Cambodia was invaded by the Vietnamese.

In those four years, Cambodia became an open-air labour camp, a kind of group of rural cooperatives. All Cambodians were forced to become peasants. For the Khmer Rouges, the only type of “pure” society was the peasant society, and Cambodians had to start right from there. The schools, offices and hospitals that had been active during the past regime were abolished. The labour in the fields was exhausting and could last even more than 12 hours for just two bowls of rice broth, one at lunch and the other one at dinner. We all suffered from hunger badly. The regime, i.e. the party directive, the Angkar, sought to create a new society by using the communist ideology. The year Zero started for Cambodia. In order to achieve the goal, they needed to destroy the structure of the old Cambodian society, the family itself had to be dismembered. Kids were separated from their families because only the Angkar owned the ideal educational method. Life, deprived of family love bonds, was very harsh. Although Cambodia was considered a rich and prosperous country, we were starving. We did not have any opportunity to buy food because money had been abolished. Afterwards, I learned that even the National Bank of Cambodia had been blown up. Life under the Angkar was worth little or nothing and fear was widespread. No one trusted anyone else. So many intellectuals and professionals such as doctors and engineers had been murdered: the Angkar wanted to restart from scratch. I learned that many militaries of the previous regime of Lon Nol had been killed. My father, who was in the army, had not trusted the regime of the Khmer Rouges, therefore he had not handed himself over to them and instead he hid his identity and profession, while the Khmer Rouges, once seized the power, said that the Angkar needed workforce for the military apparatus. Despite this attempt to escape from the regime, fate was cruel to my father all the same: he starved some months after the seizure of power by the Khmer Rouges.

In the meanwhile, I had to change my name, forgetting the one that was given to me by my parents: from Bovannrith I became Tho, from shining gold to a vase. The name Tho (vase) was considered as humble and it was widely used by the peasants. Thank this I was spared. Many people of high social status were murdered in facts: nobles, army officials, university professors. Those who wore glasses were arrested because that was linked to a high education degree. My family belonged to the well-off middle class. My father was an army officer, but I do not remember whether he was a tennent or a captain.

The Khmer Rouge’s enemy number one was the worship places, of any faith. The majority of Cambodians were Buddhist: the Buddhist monks were not spared by the mad and cruel Angkar. I could see with my own eyes when I stayed in the labour camp Vat Ek of Battambang, people jailed inside the Buddhist Pagoda. I saw in a blink while passing in front of them, a Khmer Rouge soldier writing on a big book while he interrogated a prisoner. I lived next to the Pagoda and I heard the cries of the tortured prisoners while they were interrogated before being sent to the nearby orange plantation to be murdered.

When I arrived at the Vat Ek pagoda for the first time, I had seen some gall bladders hung up to dry. How did I know they were gall bladders? My father was a fan of cockfights. At my home, we had a small farm of fighting cocks. We ate those who were not deemed apt to fight and often I was assigned the task of removing the entrails. I wonder to what purpose they served hung out there to dry, I got the answer a few days later. One evening, a prisoner was taken out of the pagoda, they took him to the orange plantation, they disembowelled him by the means of an axe and he took the gall bladder out of his body. Soon afterwards, the prisoner bled to death. In their regressive madness, the forest Khmer Rouges had brought into the spotlight a peasant belief, according to which the gall bladder was taken out of a living person, dried and minced, could be eaten in small quantities to heal from all sorts of diseases. This is why many prisoners were disembowelled before being killed: a corpse’s gall bladder provided no effectiveness to them. In those four years, I lost many family members: my parents and 2 brothers starved; another brother of mine disappeared, I had taken him to a sort of an orphanage, a place where he was fed properly. Later I learned that he had been taken into care by a nurse. As to me, in those years I had very poor health: I had attacks of malaria fever and hunger oedema. I thought I would not survive.

In 1979, Vietnam’s soldiers arrived to Cambodia. I decided to flee, following a group of labour camp inmates to undertake a long journey to Thailand. After a time of wait near the border, I had the opportunity to be moved to one of the refugee camps scattered along the Thai border. I never came across the “Righteous” in my life, but I met many people who somehow gave me much, with their generosity and humanity. I remember, to this regard, a Khmer Rouge. I was hit by violent dysentery, a bacterial infection that flakes the intestinal mucosa. They treated me with traditional medicine pills made of tree bark, and, I suppose, kneaded with flour. They tasted horrible, they were disgusting. I suffered from excruciating pain and I defecated many times a day, expelling flakes of intestinal mucosa with a lot of blood. There were no latrines and I hid among the trees. The Khmer Rouge soldier saw me, I was sick and I thought he would kill me. Instead, he was very kind. He noticed my disease and he promised he would bring me a chemical. Some days later he brought me a box of true antibiotic, like those in a modern chemist’s. Three days later I was healed. I was happy.

A person to whom I am very close and to whom I owe a lot, as she gave me the opportunity to come to Italy and start a new life, is the Italian doctor Sandra Scrimali. I met her in Mairut, a refugee camp situated at the border with Thailand and close to the seaside. She was from Pisa and had come to Thailand via the CARITAS, soon after graduating in Medicine. I met with her while I was working as an interpreter. Dr Scrimali took care of my demand to exit the refugee camp: we all were seeking somebody who would help us emigrate. She told me she would help me study and learn a job, once I’d come to Italy. I was happy, and I accepted her proposal. I wrote to my uncle, who had managed to reach the US, for his opinion. He said he was in favour of it and he would tell it to doctor Scrimali, as well. I arrived in Italy in 1980, after spending about one year in different refugee camps.

In 1984, I left the family of dr. Scrimali, who could no more host me, as her father was very ill. Thanks to a friend, I met father Severino Dianich who at the time was a parish priest in Caprona, a small village near Pisa. We had a common fate: he was a refugee from Fiume and I was a refugee from Cambodia. As soon as father Giuseppe knew that I could no longer be hosted by the Scrimalis, he offered to help me, welcoming me in the parish house of Caprona. I lived with him for about 11 years and it was one of the happiest times in my life: the house where we lived is surrounded by green fields and plantations; a few metres away flows the river Arno and in front of it there is the Romanic Church dedicated to Saint Julia, while beyond you see the charming scenario of Mount Serra. Father Severino was like a father to me and he had a determinant influence on my education. With his economic aid, and one of other generous parishioners, I kept on studying at the university and the prediction of the woman I had met in the refugee camp came true: I became a doctor.

As a conclusion, I remember my parents. It is also thanks to their example that I managed to overcome the trauma occurred in my adolescence during the Khmer Rouge regime. I lived with them a happy and loving childhood. My father was very careful and longsighted: he did everything possible to let me have a good education and above all learn the English language very well. My English knowledge helped me find a “rescue way”: arriving in Italy and being able to study to become a doctor.

The Jaca Book publishing house of Milan published in January 2019, a new edition, History collection, of my book Cercate l’Angkar – Il terrore dei Khmer Rossi raccontato da un sopravvissuto cambogiano (Look for the Angkar – the Khmer Rouge terror told by a Cambodian survivor). The book arose from my meeting with my friend Diego Siragusa, who has managed to tell my story.