One of the Chinese passports the Jews were provided with by Ho Feng Shan

“The Garden of the Righteous of Milan is launching a moral message to Europe: the politics of hospitality, along with a global plan to economically support the African countries – from which most of the migrants to our coasts come – can mark the political future of the community”. With these words Gariwo Chairman Gabriele Nissim explained in July the motivations behind the choice of the figures who will be honoured at the Garden of the Righteous of Monte Stella Hill on the occasion of the next European Day of the Righteous.

These include also Ho Feng Shan, Chinese consul to Vienna who, after the annexation of Austria to Germany in 1938, provided the Jews with expatriation visas – thus allowing them to get into safety – while all other diplomatic corps rejected them.

Many of these Jews found shelter in the city of Shanghai, under the Japanese occupation, where no passport was demanded for access. It is estimated that, between 1933 and 1941, nearly 20,000 Jews arrived in Shanghai. The massive inflow ended with the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbour in December 1941.

In July 1942, Germany proposed the “final solution” to the Japanese authorities, allied to the Axis. The request had no follow-up, and the Japanese created a designated area in the district of (Shanghai) to gather the refugees. The former synagogue of the city now hosts the Museum of the Jewish Refugees of Shanghai, that curated the exhibit Gli Ebrei a Shanghai, organized by the Confucius Institute at Milan's Holocaust Memorial from 18 September to 31 December 2016.

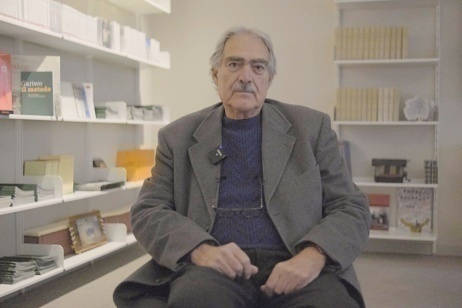

The tale of the Jews of Shanghai has also been, since 2012, at the core of Ye Shanghai, a project combining the pictures of the city at that time with sound, music and voices of the survivors. With composer and director Roberto Paci Dalò, author of this performance, we talked about the birth of this project, the figures of the Righteous and the importance of making remembrance, not only to narrate the past, but also to reflect on what is happening now in the world that surrounds us.

Let us start from 2012. How was Ye Shanghai created?

The project was initiated upon invitation of SH contemporary, a fair of contemporary art based in Shanghai, and its director Massimo Torrigiani. Little before arriving in Shanghai, in May 2012, I discovered some traces of the history of the ghetto – an almost unknown episode, also within the Italian Jewish world. Davide Quadrio and Francesca Girelli (Arthub) organized a workshop that I curated at Fudan University. Together with a group of students and professors, we started reflecting on these events, and we decided to tell this tale because it was great, also for its symbolic value.

In the Thirties and Forties, frontiers were closed all over the world: nobody wanted to host the Jews who were fleeing persecution. The only open place was Shanghai, a harbour, a chaotic and divided city – even more so after the Japanese occupation – and yet cosmopolitical, in which the Jews escaping from Europe were demanded neither visas nor papers.

Most refugees embarked from the Italian harbours (like Trieste and Genoa) on the cruise boats of the Trieste Lloyd, and after nearly 23 days of navigation they arrived in Shanghai. It is nice to be able to talk about this story, not only to enable people to discover something new, but above all because there are events that stem from a tragedy and ended in a positive note. The Jews in Shanghai have had no particular problems, and the very fact that the Jewish community of this Chinese city died out, was just natural and gradual: people, in facts, left for the United States, Palestine, Canada or back to Europe.

Your project includes pictures and sound of those times. How did you construct your performance?

Pictures of the Ghetto are very rare. I though found a collection of images at the British Film Institute of London. They are still in 35 mm, of the Shanghai of those times, and, although they are not closely linked to the Jewish community, they show the melting pot of Chinese, Japanese and European people.

The work I sought to carry out was all about sound, which is after all the narration of the tale. To achieve this, I used also the voice of a survivor, interviewed in the United States, who tells about her arrival in Shanghai from Vienna when she was about 6 years old. We thus hear the voice of an elder woman, who though watches the events with the eyes of a girl, and this is something very strong.

I used this conversation and distributed it along my work, creating a kind of a time machine. There are also some different sounds recorded at that time, which I have found online thanks to my local team, and a very famous Chinese song, Ye Sanghai (The nights of Shanghai), which I deconstructed and reconstructed until I made it a texture, from which sound and voices emerge.

What struck you the most in these events?

Above all, hope. “Everything is possible”, this tale seems to suggest.

And then paradox. Those who fled Europe in facts left everything behind, took away only a few things, crossed the borders and spent 23 days on a lush cruise boat, to then land amidst an even greater poverty. In Shanghai, in the end, a kind of bubble was created in which, far from Europe, people rebuilt a life, which was somehow similar to that of their places of origin: many languages were spoken, there were magazines, newspapers, cafés, restaurants… Something of an epic.

Besides all this, in the end, I was also struck by the sense of solidarity and community, which was very strong there.

Interesting is then the relationship with Japan. The Japanese authorities belonged to the Axis, but never applied the final solution as requested by the Nazis; in Shanghai, the Japanese Governor looked after the relations with the Jewish community, toward which no particular violence was actually exerted. From a diplomatic point of view, I think this attitude was very important, because the agreements with the Nazis were somehow left disregarded.

On the next European Day of the Righteous, in the Garden of the Righteous of Milan, we will honour Ho Feng Shan, the Chinese consul to Vienna, who provided the Jews with forged papers to rescue them from deportation. In your opinion, which is the importance of remembering these figures?

I will answer with question by another question: How important it is to think freely, if confronted with a context that apparently pushes you in one direction only? In this sense, these tales serve the purpose of urging people to reflect and be aware of what happens, see things on a broader scale and not adhering passively to mainstream.

Many Righteous people have found themselves nearly by chance as compelled to make a choice, they have often acted because one of their acquaintance was a Jew and asked for help. Racism works by exploiting the leverage of estrangement, and when you meet the other you will not define them anymore based on their belonging to some tribe or religion, because they acquire their own individual character.

Telling about these tales thus has a pedagogic component, which is pivotal to learn more about the past and see it at work in a “living” present, to understand that what happens today – albeit in different forms – is not different from what happened then.

In another project of yours, 1915 The Armenian Files, you precisely underlined this concept by talking about the Armenian genocide…

The Armenian genocide, albeit better known than the tale of the Jews of Shanghai, is not recognized by most countries, due to geopolitical reasons and economic interests.

The project 1915 The Armenian Files was set up on the 100th anniversary of Metz Yeghern in 2015, with a work that also involved Sargis Ghazaryan, the then Ambassador of the Republic of Armenia to Italy, and Boghos Levon Zekiyan, the current Archbishop of Istanbul. We have immediately agreed on methodology: we would have to talk about the Genocide in a clear-sighted way, not only to commemorate, but above all to inform the people.

And informing the people means understanding that what happened one hundred years ago is still occurring in the present, even in the same lands. If you talk about the Armenian genocide, thus, discussing it means building a system to use as a framework to reflect on all is happening around us today – thus also on the other genocide cases – in such a way not to run the risk of remained ethnically tied up to such a delicate issue.

Talking about the Metz Yeghern or the Holocaust means of course telling about the events in connection to a people, but this serves the purpose of setting into motion a broader reflection.

Just like Hannah Arendt told us about the "banality of evil", in my opinion we can act in order to build the “banality of good”, designing a viral system and spreading such a “virus” in society, also through the use of key words that shall be able to let us open our minds, suddenly showing us something under a totally different light.

As far as key words are concerned, how should we start this “contamination”?

First of all I would start from key actions, made of attention and community. Thus paying attention to the tiny places we found ourselves in (be them the classroom, the road, our jointly owned building, or the workplace), and thanks to this attention become aware of the presence of the others. The simple fact of becoming aware of a presence can set into motion an unstoppable and positive chain reaction.

CDs Ye Shanghai and 1915 The Armenian Files are published by Marsèll. The Ye Shanghai DVD is forthcoming.

Roberto Paci Dalò – composer, director and visual artist – runs the group Giardini Pensili, which he has presented his works with in theatres, museums and festivals all over the world. Gis work has been appreciated and supported among others by Aleksandr Sokurov and John Cage. In 2015 he received the Premio Napoli for the Italian language and culture. He is a teacher of Interaction Design at UNIRSM (Università degli Studi della Repubblica di San Marino), where he is a founder and manager of Usmaradio. He was born in Rimini, he grew up in Tremosine on the Garda lake and he has lived in Berlin, Naples, Rome, with long times spent in Vancouver.