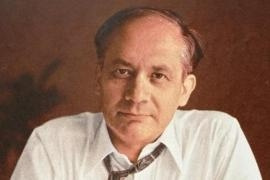

Raphael Lemkin

27th January 2021, International Holocaust Remembrance Day - Below is the speech held by Gariwo President Gabriele Nissim at the Commission of Foreign Affairs of the Italian Chamber of Deputies during a hearing on the prevention of Genocide.

President Nissim put forward a proposal to take a further step towards fulfilling the commitment made by Italy when it signed the UN Convention on the Prevention of Genocide on 2nd August 1953, and towards keeping the promise of “never again”.

On 27th January, when the extermination of Jews is remembered throughout the country, it is important for the Italian Parliament to reflect on how remembrance of the Shoah has changed the world and has led to new beliefs.

First of all, two new words were born and entered the vocabulary of human beings.

What Churchill called a nameless crime, as it escaped any type of imagination and met with the incredulity of those who did not want to see, has now a word defining it. First the term “Holocaust” was used, then, considering that such word suggested the idea of a “sacrifice”, the word “Shoah” (meaning “catastrophe” in Hebrew) became more appropriate.

However, as Israeli historian Yehuda Bauer observed, it was important to explain its characteristics: an unprecedented massacre due to its mode of operation conceived by an ideology that, considering Jews as enemies of the whole of humanity, wanted to annihilate them to the last, everywhere.

Secondly, thanks to Polish Jewish jurist Raphael Lemkin, the word “genocide” was coined in 1942 (while the final solution was in progress): it consisted of a Greek and a Latin word (“genos” and “cide”), to indicate the will to destroy an ethnic, religious or social community.

He wanted a clear and accurate word (“like Kodak brand for cameras”) that everyone could remember to indicate the extermination of a minority in both times of peace and war in History. That word had to provoke an immediate sense of shame and reprobation, as the commandment “thou shalt not kill” was unfortunately considered to be valid only for those within their own group, but not for others, who could thus be slaughtered without scruple.

Lemkin stated that genocide was a threat to the whole of humanity, since the destruction of any minority not only annihilated affected individuals, but also impoverished the richness of human plurality on earth. Due to this, the prevention of genocide was the responsibility of the entire international community.

Remembrance of the Shoah gave rise to important cultural and political initiatives.

For the first time, from the Nuremberg Trials to Eichmann trial in Jerusalem, the concept of “crimes against humanity” was introduced. It applies to those who obeyed and still obey evil orders in wartime, and approved and still approve extermination, becoming an instrument of it, and must be deemed to be guilty and cannot exonerate themselves by claiming they had to obey an order.

The reflections of Primo Levi in Italy and Simone Veil in France made it clear that the victims of Nazism were not only resistance fighters, but also those who were “guilty” of being born Jewish. We owe the knowledge of the abyss of Nazi anti-Semitism to proactive witnesses like them, including Nedo Fiano and Liliana Segre.

Through great battles for remembrance, for the first time in history, a path of moral purification was set in motion after genocide.

Germany took responsibility for its guilt before the world. Willy Brandt bowed before the monument to the victims of Warsaw Ghetto. After the suppressions of François Mitterrand, President Jacques Chirac, in France, took responsibility for Vichy government, which was complicit in the deportations of Jews.

After 1989, amid uncertainties and polemics, in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, where there was also complicity with Nazi barbarism or indifference to the Jewish fate, a critical reflection emerged on their past, after communist totalitarianism - having incredibly taken the path of anti-Zionism - had removed any discourse on the complicity of anti-Semites.

From Jewish prominence for international remembrance of the Shoah, other peoples such as Armenians or Rwandans moved onto the public stage to have their genocide recognised. Jewish survivors, who witnessed and fought against oblivion, set an example and gave courage to other peoples to break the wall of silence.

Such new thinking reached its high when reflection was started on the political, cultural and legal ways that could prevent and punish every new form of anti-Semitism and every new genocidal mechanism that may threaten the international community again.

It is the well-know moral promise of “never again”: what had happened to Jews was never to be repeated for Jews or for any people on earth.

The pioneer of this ingenious and innovative idea was Raphael Lemkin, who led the United Nations in 1948 to approve, after trying to do it in 1933, at the time of Hitler’s rise, an act committing to repressing and blocking any attempt to destroy a national minority.

The Convention, which he had taken care of in every detail, stated that not only acts of genocide, all forms of complicity, but also direct and public incitement to commit genocide were to be punished.

Therefore, it was not only necessary to act in the event of extreme evil, but also to prevent evil at its onset when propaganda of hatred started with violent and genocidal words.

Raphael Lemkin, who had lost his entire family in Polish extermination camps, felt that the immense trauma of the Nazi genocide should shake humanity through a Convention calling all nations to proactive commitment against any new genocide.

Redeeming victims, to whom the world had been indifferent, meant imposing a turning point, because, without any instruments of prevention and deterrence, everything could be repeated again and again.

In New York he explained to students that the historic convention had legislated an important commandment: do not commit genocide: “Conscience manifests itself with a feeling of shame. Once this feeling envelops an act of genocide, half the job is done. Moral condemnation will be easier because now genocide has become a crime”.

Unfortunately, the Convention has not changed the course of events, because since 1948 there have been over 55 genocides involving 70 million victims, according to Gregory Stanton, founder of Genocide Watch, and often the veto power of superpowers prevented its application. We all remember, for example, the terrible responsibility for the failure of the UN military to intervene, which could have prevented the genocide in Rwanda and that of Bosnian Muslims in Srebrenica.

Yet Lemkin’s Convention marked a new beginning: International Criminal Tribunals were set up to try criminals of Bosnia, Rwanda and Cambodia; the principle of humanitarian intervention (Responsibility to Protect) to come to the aid of threatened populations was affirmed; discussions started at the United Nations on an early warning system to inform the world when there are grounds for genocide.

If all this is implemented, remembrance of the Shoah, a paradigmatic genocide of the 20th century, will impact on the whole world, which the Polish Jewish jurist aimed at achieving.

This depends on the political will of each individual country and on the conscience of each citizen.

This is why today, as an Italian and as a Jew, I am proud to recall the intensity emerging on Holocaust Remembrance Days and the commitment of institutions in the fight against anti-Semitism, culminating in the government subscribing IHRA (International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance) memorandum of understanding.

However, I would like us to take a further step towards fulfilling the commitment that Italy made when it signed the UN Convention on the Prevention of Genocide on 2nd August 1953.

Three proposals follow:

1) appoint an Italian Genocide Advisor in Parliament who collaborates with the UN Special Advisor on the Prevention of Genocide and the institutions of the European Union;

2) commit the Commission of Foreign Affairs of the Parliament to draw up an annual report presenting to public opinion the dangers of new genocides in the world and possible measures to be taken to prevent them. The history of the Holocaust has taught us that indifference and lack of information about a crime against humanity are prerequisites for perpetrators to act with impunity and thus conceal their actions. As Lemkin imagined, it would be a matter of scientifically monitoring all the signs that are the prelude of new genocides, such as the outbreak of new violence or hate speech affecting Jews and any minority;

3) establish also in Italy an autonomous and independent human rights agency, as proposed by the European Union, which, in collaboration with the International Criminal Court, would permanently investigate the state of human rights in the world and crimes against humanity.

This commission does not exist yet, but I invite the Parliament to turn its gaze to the fate of the Rohingya people and the 730,000 civilians forced to flee to Bangladesh; to the one million Uighurs, locked up in concentration camps in the Xinjiang region; to the extermination of the small Yazidi minority perpetrated by Islamic State fighters in the Sinjar region; to the endless war in Yemen; to the African continent, where from Ethiopia, to the Sahel, to South Sudan, inter-ethnic clashes, Islamic fundamentalism and climate change continue to torment populations, leading to dramatic situations.

This is the spirit of my speech: telling the story of forgotten genocide and conflicts on Holocaust Remembrance Day, to actually give shape to the promise of never again.

Published on 27th January 2021 in the Italian daily newspaper Avvenire