In short

From 6 April to 16 July 1994, Rwanda was the scene of the genocide against the Tutsis and the moderate Hutus, perpetrated by the regular army and the Interahamwe, paramilitary militias. The main ideological motive behind this was racial hatred against the Tutsi minority, which formed the social and cultural élite of the country. In only 100 days about a million people died, murdered above all with machete, axes, lances and maces. The extermination ended with the military victory of Fpr, the Rwandan Patriotic Front, which was an expression of the Tutsi Diaspora.

History of the country

The region of Rwanda – Urundi had been unified in the 16th century by the Tutsis, who had founded a feudal monarchy, subjecting the Hutus and the Twas, the other two ethnic groups of the area. Tutsis, Hutus and Twas continued living together on the same territory, sharing the same language, religion and culture.

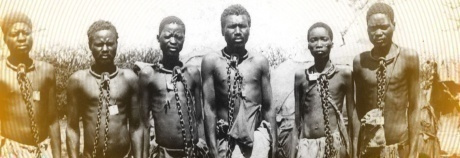

The country, that was explored by the Germans at the end of the 19th century, in 1924, upon mandate of the League of Nations, was entrusted to Belgium. Strong in their belief in the physiognomic theories of the 19th century, the Belgians, in the colonial exploitation, relied on the tall, slim, light-skinned Tutsi, whose physique close to Western standards suggested that they were more intelligent and suited to ruling, while the stock and dark-skinned Hutu were thought to be more suited fo toiling in agriculture. The Twa, who were pygmies, were overall considered as similar to monkeys.

In 1933, Belgians would insert the indication of the ethnic group on the Rwandans’ identity cards. The Belgian support to the Tutsi ended in the 50es, following the unrest caused by the colonial exploitation, which led the Hutu to rebel against the Tutsi and the latter to plan the independence of the country from Belgium. The colonizers would then decide to back the Hutu rebellion.

The genocide’s planning and warning signs

In 1957, a group of Hutu intellectuals founded the Parmehutu, the party for the affirmation of their own group, which published the “Manifesto of the Bahutu”, in which the racist monopoly of the Tutsi power was exposed, and a social revolution based on the Hutu’s racial superiority was put forward.

In the 1960s, the affirmation of the Parmehutu led to the abolition of the monarchy and the proclamation of the republic, with Gregoire Kayibanda, who set up a racist regime. The persecutions against the Tutsis started. These were compelled to seek shelter in the neighbouring countries; they would continue also in the regime of Juvénal Habyarimana, who went on power in 1973 with a coup, promising progress and reconciliation.

In 1987, the Tutsi Diaspora gave rise to the Fpr, the Rwandan Patriotic Front, run by Fred Rwigyema and Paul Kagame, with the aim of favouring the refugees’ return into the homeland, if necessary through the military seizure of the power.

The end of the 80s saw Rwanda amidst an economic crisis: in the face of a strong demographic increase, the country’s agricultural resources remained unvaried and the only source of income. The inner pressures, combined with the Western demand for democratization, led President Habyarimana to launch in 1991 a new Constitution, which promised a multi-party system.

While the Fpr guerrilla continued, with massacres from both sides, on 24 August 1993 the President signed the Arusha accords, that provided the return of all Tutsi refugees, and a substantial partition of power with Fpr.

From that moment on, the true planning of the genocide started: the Akazu, “the little home”, the power group that had formed around President Habyarimana and his family clan, started to organize itself. The interahamwe, “those who work together”, irregular Hutu militias, were created and armed; lists of Tutsi exponents to kill were compiled; through the Chillington firm of Kigali, machetes were bought from China; “Radio Machete”, the nickname of the Free Radio Television of the Thousand Hills, was set up to coordinate and incite the Hutus to “complete the job” of extermination of the “cockroaches”.

All this with the financial and military support of France.

All the Hutus were called to take part in the genocide: those who did not take part into the “job” was considered as an enemy and thus had to be eliminated.

French soldiers on patrol pass by ethnic Hutu government troops near Gisenyie, 27 June 1994.

Théoneste Bagosora a Goma, nella Repubblica Democratica del Congo orientale, 21 settembre 1994.

Features of the genocide execution

On 6 April 1994, Habyarimana was coming back from Dar es Salaam, where he had agreed upon a new composition of the cabinet, as the presidential plane was shot down by a missile while landing in Kigali. It was the start of genocide.

The ultras of the Hutu Power, led by colonel Théoneste Bagosora, chief of cabinet of the Ministry of Defence, spread a list of 1,500 people to be killed first. The interahamwe entered the action, and set up road blocks: at the control of the documents, the people whose papers indicated they were Tutsis were massacred with thrusts of machete. The radio coordinated the operations, spread news and exulted at the most spectacular actions, and invited the Tutsis to present themselves at the blocks to be murdered. The interahamwe militia men shot the people dead, but in most cases they killed them with machetes, axes, lances and spiked maces. There were no safe places for the Tutsi: also the churches were violated.

In April, the Europeans were evacuated from Kigali and the United Nations decided to withdraw the peace contingent, while the issue whether it was genocide or not was being debated. Only a few Blue Helmets remain, witnessing powerless to the bloodshed that was perpetrated before their eyes, while their commander, general Romeo Dallaire, demanded reinforcements in vain.

On the hills of Bisesero, dozens thousands people organized the resistance.

On 22 June, the French stepped in with a military action, ”Operation Turquoise”, later defined as humanitarian and recognized by the UN, actually originally designed to counter the advance of the FPR and therefore in support to the Hutu regime. This intervention would also be exploited by the culprits of the genocide as a cover-up for their runaway from the country.

On 4 July Paul Kagame, at the head of the Fpr army, entered Kigali. On 16 July, the end of the war was officially declared.