Charter for social media

Web reality. Tips for online awareness.

“Words are stones, words can turn into bullets, we need to weigh every word we say and stop this wind of hatred”, Andrea Camilleri

The power of words

We live in a society where everyone, no matter where they are or what their job is, can become an actor in global communication. Thoughts in the digital world are fast, contain few words and many images and can be made public at any time. However, these opinions do not always stem from actual awareness of the power of words and of consequences they can have on other people, in society, in politics, in education.

Language is the distinctive trait of human beings. It marks our identity, allowing us to forge relationships and describe the world that surrounds us, even more so in the web, where gestures, facial expression or the tone of the voice cannot help us. This is why our role in the community makes it an act of responsibility to consciously use language, which starts from the so-called digital civic education in the web.

Starting from digital civic education

Starting from the assumption that virtual is real – the web is a tool of social, cultural, economic and political involvement in the life of citizens as statements and gestures made in person are - the classical concept of civic education must also be extended to the digital world. The previous one must not be replaced but rather complemented, updated, including technological innovation that has entered our daily life.

The communication potential of social media is huge, new generations more than anyone else can benefit from sharing of ideas, conversation and can stimulate their curiosity through an interconnected world that a few decades ago would not have been imaginable. Uncritically accepting whatever one reads in the web, however, leads to a strong risk for “viewers/actors”, who can both run into manipulated, inaccurate or unfounded information, and frequently be the victims or see cases of hate speech, when language is used to convey messages of hatred and ethnic, religious, gender, sexual orientation discrimination and so on so forth.

The keywords of this educational approach, as stated in the Curriculum on Digital Civic Education issued in January 2018 by the Ministry of Education are: critical spirit and responsibility. In creating a critical spirit among young users of the Web - and among their parents, who in most cases learn from them - school and dealing with education and culture play a pivotal role in different ways. Their task should be to raise awareness on human rights and to disseminate a method to survey sources that can act as an antidote to the “dark side” of social media, consisting of hatred, discrimination, aggression, racism. Furthermore, teachers can teach students not to consider the Web as a harmless relief valve but rather as something in which the same rules and the same consequences of human behaviour apply and can give them the tools to build an inclusive and dialogue-based global culture, through the knowledge of History, the study of cultures, appropriate use of their mother tongue and of foreign languages, a method to use respectful and positive conversation. In order for this to be possible, teachers must necessarily be trained before educating students; teachers must be trained on the new digital education to be able to convey it in classrooms.

In this sense, the viewer/actor pair is a clear focal point to understand the concept of ethical and conscientious behaviour in the digital world: if we only believe we are viewers, we cannot realize that everything we put on the web is indelible, that it helps creating our online curriculum, that is the image of our person. And above all, it has a positive or negative impact on those who read what we post and we therefore have a human, professional and also legislative responsibility towards them. On social media and in the Web in general, we too often feel entitled to express anything we think without reflecting, and sometimes even to write things that we would not be willing to repeat in another context. We are part of what Marc Prensky calls cyberstupidity, that is being online without thinking about the consequences of our actions.

For these reasons it is crucial to timely educate young people to dialogue, to the responsibility stemming from being part of a global world, to the idea that when we choose a word and not another one, we are not only expressing a linguistic preference, but representing ourselves in society.

The grey area of the Web: monitoring online debate leads to doing it in all contexts

Being online consciously, now that we are all potential producers of news even though we are not all professional journalists, means not only reflecting on what we write and ensuring respect of other people’s rights, but also dealing with hate speeches without feeding what Stefano Pasta, a researcher at CREMIT, defines as the grey area of the Web, that the area where no action is taken, reported and we are simply observers.

Indeed, recent research shows that especially youngsters recognize hate speech but do not act, because they do not think they have to do it. The task of monitoring and countering hate speech, however, should not be only the responsibility of the state or of a cyber police - as stated in the Manual on combating hate speech through human rights education of the No Hate Speech Movement of the Council of Europe - but should also include actions that each user can actually do, becoming a rescuer in the event of hate speech.

Among these actions appears providing an alternative to violent language, a positive counter-narrative, using the language of human rights; trying to dispel prejudice or incorrect information that can affect a group or an individual; reporting abuse if it occurs; telling victims of injustices what their protections are. What is more, if you are a victim or a witness of hate speech, telling what happened on a blog or social media - not spitefully but rather proposing a positive alternative - can help other victims and can raise awareness in those who used hate speech on the impact of their thoughts, because it is also important to take care of haters.

Besides the content, it is crucial to keep an eye on the form in which it is expressed on the Web. Too often, indeed, we read on social media some statements that look more like sentences and exclusive truths, which seem to be aimed to convince and not to discuss. Conversely, it is doubt-based dialogue that can actually make the communication potential of the Web bear fruit constructively, making it a place of positive confrontation where one can learn good practices to be replicated also in other areas of life. Virtuous behaviours on the Web are therefore numerous and are always evolving as online universe is; what really matters is understanding that the Web is not a screen we passively observe, but rather a stimulating reality where we have rights, duties and potential.

Besides companies dealing with the Web, the scope of responsibility in the digital universe does not only include common digital users but also information professionals from the world of journalism, for whom online communication has become the main channel. Something that is not always known about this context is that communicating via the Web and social media does not necessarily mean having the opportunity of being more “superficial” or of simplifying; it also means being faster and shorter, definitely, but always respecting the content that is being disseminated. Especially when talking about sensitive issues, currently including migrations and racisms, summarizing complex issues using sensational statements about the topic, which are not exhaustive or even evoke commonplaces to snatch more sharing, can be very risky.

It is not possible to know what path a specific content will follow, how much or where it will be shared, it is therefore essential not to fall into underestimation of its communicative power. A crucial example is the narrative on the “invasion” of migrants, which has been echoing in Europe for more than five years: based on data available, we know that it has not involved such a large number of people to justify use of this definition – temporarily leaving aside ethical implications - but this is what many have perceived and some media have actually contributed to it in part.

Disinformation and fake news have always existed and what has changed is that now digital communication allows for faster and above all more “targeted” dissemination. Information indeed affects specific groups of people and markets. Just think of the storm that broke out over the election of Donald Trump, which was allegedly facilitated by a deceitful and denigrating social media campaign aimed at raising negative feelings towards his opponent, Hillary Clinton, in thousands of potential voters. Today more than ever, therefore, information professionals must keep the substantial truth of facts - which does not certainly aim at being absolute truth, but at defending the right of individuals to founded information, not biased by a different type of interests, expressed as dialogue and not as an obligation.

The illusion of knowing

Umberto Eco, already an investigator of mass culture provocatively affirmed on social media: “Social media give freedom of speech to legions of imbeciles who used to only speak at the bar after having a glass of wine, without harming the community”. This extreme vision of social media paves the way to reflection: online messages are basically indelible and are read by an extremely vast public that cannot be controlled or quantified. Combined with the huge availability of information of the Web, this makes the illusion even stronger of having and boasting authoritativeness on issues or in contexts that are not actually known. Endless discussions, fake news and even hate speech can therefore be triggered, precisely because we tend not to recognize those who express a competent and founded opinion on a certain theme and those who do not. The other side of the coin is that readers who can conversely be authoritative in expressing their own vision on a certain topic or have a very large audience, must consequently pay even more attention to what they post on the Web, since not only people who trust what they say can take them as a model, but also their opinion, among the many “not competent” views expressed, will resonate even more. Authoritativeness therefore implies even greater responsibility, amplified by the potentially endless public of the Web.

How much democracy is there in the language of the Web?

Digital democracy, that is the exercise of democracy using digital tools in communication and political involvement, has been gathering for many years the expectations of many, who considers it to be an opportunity to overcome the shortcomings and crises of global democracies. It is precisely on the conflict of ideas and the opportunity for everyone to express their opinion that democracy is founded, which would therefore seem to have found its highest expression in the online world.

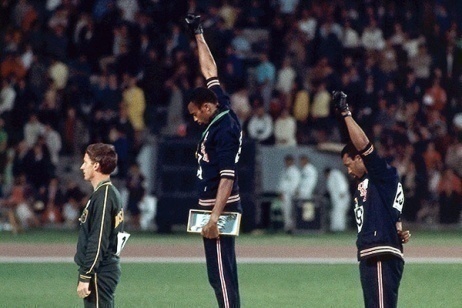

However, although there is no doubt that online interaction is democratic and cannot be censored, we can say today that the boundary has proved to be very thin between free expression and use of the Web to annihilate any other visions. Digital democracy exists as long as other people’s rights are not harmed, which must be protected from imposition of ideas or fake news and pre-established narratives. In this scenario, we often see that hate speech is hurled against individuals not so much because what they express is not appreciated, but rather because individuals themselves are not appreciated, due to groups they belong to, their skin colour, their social status, their political ideals: “The problem is not what you think, you are the problem”.

Indeed the Web has also come to strongly affect the way of doing politics. Tweets have replaced speeches in the streets, have made them much more immediate, have given them a more subtle and playful way to reach people. Once again, this can facilitate political involvement of all subjects of civil society, but can also make the life easier of unscrupulous politicians who produce or ride waves of poison to foster their own interests at all cost; who use words that seem to stem from very precise ideologies while pretending that fascisms and totalitarianisms no longer exist: “It is just an analysis of reality, it is not a matter of ideology”, we often hear.

"A formal commitment to responsibly use the media, first of all taken by members of the state, would be a small step forward in building a more civil, healthy and productive public arena”, reads an appeal to parliamentarians and to the Government launched in September 2019, among others, by Pier Cesare Rivoltella, Director of CREMIT, Pier Giuseppe Rossi, President of SIREM and Andrea Garavaglia, Professor at Milan Università degli Studi. Politicians cannot disregard conscious use of language, cannot fall into trivial and vulgar conduct, particularly if such conduct becomes the tool to “mix” with people and convince them of the existence of new, more honest truths: those that hinge on emotions of people to the detriment of rationality.

Good emotions of good stories: contagious beauty

Protection of human beings from the multiplication of hate and intolerance speeches therefore finds its best allies in ethical information, in education and in the effectiveness of positive examples. And it is in these very conditions, in particular, that the stories of the Righteous come into play, as the positive emotions they convey can teach us that individual decisions to act have an inestimable value. The Righteous are good teachers. This is why sharing their virtuous example on the Web, becoming ambassadors of their courageous good deeds, of their contagious good, can not only help prevent hate speech, but also help strengthen democratic behaviour both online and in personal life.

Therefore one should not be a Web specialist to give a positive contribution online and an alternative language to hate: each individual can make the difference. And last but not least, conscious use of language and vocabulary has not lost its importance in the digitalised world, it has rather taken on exponential relevance. Digital communication has become our main way to express ourselves; this is why we have the duty to learn to do it responsibly.

To foster the development of personal awareness in conscious use of the Web, Gariwo has proposed the annex to 2017 Charter of Responsibility, on social media and the Web. We are committed to embed ethical behaviours and dialogue-based attitudes in our mission.

- Consider that what you write on social media and on the Web has a great impact in society: it can improve people’s behaviour and bring them closer, or generate hatred, feed the enemy’s culture, exacerbate conflicts and raise walls. Discussions on social media are not a world apart, but rather leave deep traces in our relationships, in politics, in daily life and define our public image.

Whoever uses hate speech or is influenced by bad teachers, will trigger negative behaviours in society, which will be replicated in different contexts of reality. - When you have an opinion or a judgment to be expressed, do not think that it is always the truth, or that those who have different opinions are in the wrong or are evil. Always express yourself gracefully and do not fall into the logic of insults and personal invective. Always think of the beauty of dialogue among friends, where everyone can be enriched by exchange with each other.

You must imagine that with your personal contribution, the Web can become a great place to educate to sharing your common destiny, to bring people of different cultures and religions closer, to overcome contrasts raised by nationalisms and fanaticisms. Through the Web one can learn the pleasure of being part of a shared world, without barriers, and then contribute to educating towards a democratic spirit and a taste for dialogue. Democracy indeed is not an abstract container: it needs human beings used to respectively dealing with the others to work effectively. - Do not be passive when you observe that on the Web someone attacks others, sows contempt, racial hatred, anti-Semitism or launches crusades creating imaginary enemies. As it happens in relationships between people in flesh and blood, you can be a rescuer in the event of hate speech on the Web. You can try to educate with an open and benevolent spirit those who do not understand the pleasure of conversation and who use hostile language.

If you remain silent, you will leave room to haters, who try to turn online debate nasty and social media into a place of dissemination of the enemy’s culture.

Be aware that even individual actions can become a barrier and a sentinel against evil. - When you express your opinion online, you must be aware of your knowledge and, if you realize that you are not competent on a certain topic, you can choose to take an open and constructive attitude or, sometimes, not to express yourself, so that you do not risk spreading disseminating incorrect information. If, on the other hand, you are authoritative on the topic, or have a very large audience, be aware you have a great responsibility for what you post on the Web.

- At any time you can lay the foundations to stop the flow of fake news on the Web, which are produced by States, companies, and even politicians to influence public opinion, by largely investing in them. You can start by avoiding sharing or by reporting messages that appear suspicious to you. You must be aware that those who use certain tools never give thorough reflections, validated by research, but rather try to create confusion and artfully attack people to arouse in us an immediate reaction of anger and rejection. They are professionals in leveraging people’s emotions and not rationality.

- The Web is democratic if it is a place of exchange of ideas, of social and political involvement, not if it is used by politicians as a substitute for democratic institutions or to annihilate any other opinions. As individuals and citizens of the Web, you can learn to carefully observe statements made by those who exploit the simplification of multi-faceted concepts and events to convince you that there is a single credible point of view, and can instead privilege those who use consistent and open language, never a commanding one.

- A characteristic of good is that it is contagious. If on the Web you can infect the others with your dialogue-based attitude and with the beauty of positive examples, including those of the Righteous, you will therefore contrast the dark side of the Web. Telling about those who do good, those who help, those who take responsibility for something is the best way to overcome prejudice and generalization. Disseminating the story of a Righteous who fights to foster interreligious dialogue, who fights for positive and real integration, to open up to the others, to deny false prejudice, is an opportunity to reject racist stereotypes that depict minorities as our enemies. Those who hate on the Web blow on fear and on the worst instincts. Through the digital society, you have the opportunity to raise emotions by showing the humanity of all individuals regardless of their origin, their religion and their ideas.

Through your example, you can be the initiator of a chain of good that unites the best people on the Web and create a network that isolates haters and becomes a thrust for civil coexistence in society.

They joined the Charter for social media...

Paolo Bernasconi

president of Human Rights Festival and Forum

Claudio Bisio

actor

Andrea Colamedici

philosopher and creator of “Odiare ti Costa"

Federico Faloppa

coordinator of the National Table Against Hate Speech

Maura Gancitano

philosopher and creator of “Odiare ti Costa"

Vera Gheno

sociolinguist, former member of the linguistic consulting editorial staff of the Accademia della Crusca

Piergaetano Marchetti

president Corriere della Sera Foundation

Pier Cesare Rivoltella

CREMIT director

Milena Santerini

national Coordinator for the fight against anti-Semitism

Liliana Segre

Holocaust survivor and Life Senator

Nadav Tamir

former Israeli diplomat and board member of Mitvim

Massimo Zamboni

CCCP leader, now writer for Mondadori and Einaudi

They also joined...

Paola Andrisani, anthropologist; Yair Auron, historian and professor at the Open University of Israel; Jean Blanchaert, artist; Sandra Bonzi, journalist; Maurizio Cohen, lawyer and professor; Silvia Costa, journalist, former MEP; Sabrina Di Carlo, educator; Dounia Ettaib, president of the Association of Arab Women of Italy; Giovanna Grenga, teacher; Saifeddine Maaroufi, Imam, teacher and cultural linguistic mediator; Cristina Miedico, director of the Archaeological Museum of Angera; Anna Migotto, journalist and writer; Giorgio Mortara, UCEI vice president; Daniela Palumbo, writer of children's and adolescent literature and Journalist; Stefano Pasta, journalist and researcher at CREMIT; Alberto Sanna, president of the DARE.ngo Association; Luciano Scalettari, journalist; Nathan Stoltzfus, historian, professor of Holocaust studies at Florida State University; Patrizia Toia, MEP; Amedeo Vigorelli, professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Milan.